A HIGH Court judge has suggested that the covid19 pandemic be recognised as having suspended the running of limitation periods for adverse possession claims, due to the inaccessibility of the courts during that time.

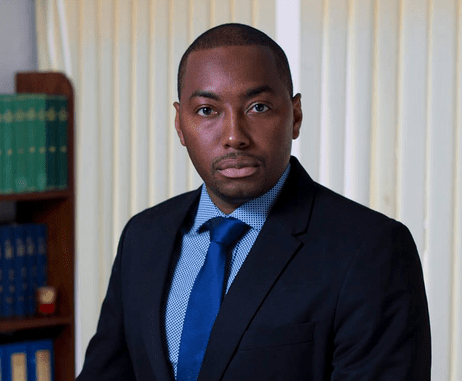

Justice Westmin James made the remarks in a ruling on a land dispute on April 8.

He opined that the pandemic’s effects on court accessibility should have suspended limitation periods – a principle not recognised under the current Real Property Limitation Act, but which, he suggested, merits legislative attention.

“I am of the view that, in the absence of legislative amendment, the common law should evolve to recognise that the covid19 pandemic effectively suspended the running of limitation periods for adverse possession during the time when the courts were inaccessible.

“During this period, landowners were unable to initiate proceedings or effect personal service of claims. Time should not run against a party who is legally barred from bringing an action.

>

“Just as the commencement of legal proceedings suspends the limitation period under the Limitation of Certain Actions Act, I am of the opinion that the pandemic should be treated as having a similar suspensory effect on adverse possession claims.”

He said the “mischief” the Extension of Limitation Period Orders sought to remedy should equally apply to limitations under the Real Property Limitations Act.

In his ruling on the land dispute, which spanned decades, he determined that the beneficiaries of the estate of Baby Seenath, also known as Baby Sumintra Seenath, are entitled to possession of a disputed parcel of land in Belle Vue Estate, South Oropouche and damages for unpaid rent from Verna and Dindial Ramlakhan.

The claim centred on Lot #36, part of a 38.78-hectare parcel of land. The six claimants, the heirs of Baby Seenath, who died in August 2009, sought possession of a commercial lot, removal of a structure erected by the Ramlakhans, an injunction to prevent further trespass, and $2,400 in unpaid rent accrued over six years before the formal transfer of the estate.

The Seenath clan claimed ownership of the land through a deed of assent and longstanding possession by the deceased.

They argued that the Ramlakhans had entered and remained and had ceased paying rent in 2005. The Ramlakhans’ counter-claim of adverse possession was dismissed by the judge, who held that payment of rent in 2005 restarted the limitation period.

He noted that under the law, adverse possession must be continuous for 16 years from the last acknowledgement of ownership, which, in this case, was from March 24, 2005.

Justice James also noted that while the Ramlakhans claimed exclusive possession, they admitted to being tenants of the Baby Seenath and paid rent, the last recorded payment being in 2005. This, combined with communication between the parties in 2007 and litigation in 2012, confirmed their acknowledgement of the Seenath clan’s title.

"The defendants are estopped (prevented) from asserting that the claimants do not have title,” Justice James ruled. “A tenant cannot deny the title of their landlord absent a competing claim, which is not present here.”

>

He also held, “The claimants have been deprived of their property and, in the absence of any other evidence, are entitled to the rent for the six years prior to the deed of assent owed by the defendants to the first claimant as legal personal representative of the estate of the deceased.”

He ordered the Ramlakhans to pay the $2,400, plus interest and ordered them to give up possession of Lot 36. They were also ordered to remove any structure on the land at their own cost before July 31 and granted an injunction preventing further trespass.

Attorneys Roger Kawalsingh and Victoria Seenath represented the Seenath clan while Mohanie Maharaj-Mohan represented the Ramlakhans.