Senior Reporter

Hundreds of regional and international energy stakeholders gathered yesterday at the Hyatt Regency for the Energy Chamber of Trinidad and Tobago’s annual conference, but the most striking presence was the absence of state-owned energy companies and government officials.

The boycott followed a sharp intervention last week by Prime Minister Kamla Persad-Bissessar, who launched a scathing attack on the Energy Chamber, accusing it of serving foreign multinationals and narrow special interests while marginalising local contractors and undermining state-owned energy companies.

The Prime Minister also announced the withdrawal of the Government’s support for the conference and the removal of state-owned enterprises from participation in response to concerns surrounding the Safe To Work (STOW) certification programme administered by the Energy Chamber.

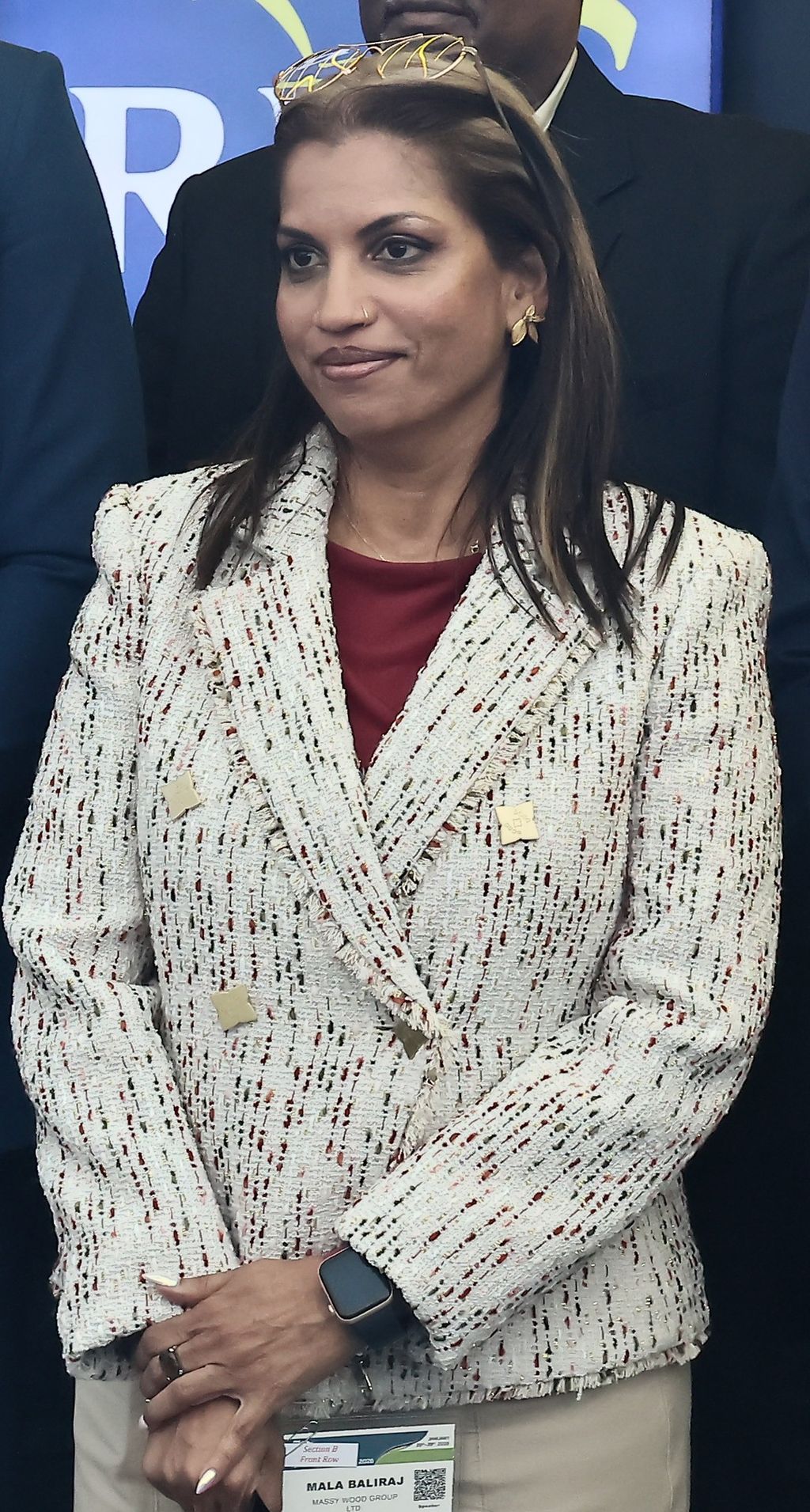

Addressing delegates yesterday at the Hyatt Regency hotel, Energy Chamber chair Mala Baliraj acknowledged the backlash and signalled a shift in tone, committing to reflection, review and reform.

“We got some tough feedback. I will also note that, in the spirit of constructive feedback, we have taken the message to heart. We have committed to reflect, review, and make changes as needed,” Baliraj said.

She said the chamber intended to reposition itself to facilitate structured engagement with the Government and other stakeholders.

“Our intention is always to work towards a collaborative approach with all of our stakeholders. As such, we hope to be able to reposition and create a space for open and structured engagement with the Government that supports the best outcomes for the sector,” she said.

Baliraj expressed confidence that changes would lead to improved outcomes, adding that the chamber remained committed to engaging all stakeholders, including state enterprises.

“We place the intention that over time, we can return to a situation in which state enterprises, Ministry of Energy officials, and other state players can participate in this valuable space,” she said.

She outlined that the chamber had always valued their contributions and hoped to welcome them back. Baliraj said it was not practical to address every issue raised over the past week but identified three matters central to the chamber’s purpose.

The first was the Safe To Work programme, which she said had become a point of contention among stakeholders who believed it no longer met its original intent.

“Some stakeholders do not believe that the Safe to Work programme is meeting its original intent, to both improve safety standards and to facilitate the ability of smaller local contractors to pre-qualify with major operator companies,” Baliraj said.

She acknowledged concerns that the programme had at times served as a barrier to doing business, particularly due to costs associated with consulting advice and staff training.

Baliraj said that given the Prime Minister’s position, the current configuration of contractor safety management certification would not be maintained.

“What comes next for contractor safety management and certification must be built on the best elements we have as an industry and improve the areas that do not work well,” she said, adding that this must be achieved through consultation.

She stressed that safety standards could not be compromised. “Our industry needs robust, high-quality safety practices to be maintained. This is not a theoretical issue but a day-to-day operating reality,” she said.

The second issue addressed was the perception that the Energy Chamber is dominated by multinational corporations.

Baliraj said the chamber’s roughly 400 members included companies of all sizes and ownership structures, and that governance mechanisms were designed to prevent dominance by any one group.

“Given the current perception, we clearly have to do better,” she said, committing to a review of internal governance to ensure balanced representation.

In response, former energy minister Carolyn Seepersad-Bachan told Guardian Media that the creation of a single safety certification system had been well intentioned but flawed in execution.

“The Energy Chamber needs to establish a standardised and recognised certification programme to replace the many company-specific regimes that existed before was a step in the right direction. However, if it were properly designed, a single certification programme should not increase costs; it should reduce them, while strengthening safety culture in this country and improving international credibility.”

Bachan said any system must balance safety with fairness. “Any standardised certification programme must balance two equally important objectives–rigorous safety and quality assurance. And secondly, accessibility and fairness, so that compliance does not become a financial gatekeeping mechanism,” she said.

Seepersad-Bachan said an independent body was required to preserve legitimacy and public confidence, insulated from commercial interests and governed by transparent rules.

She said collaboration between the Government and the Energy Chamber was essential to determine what replaces STOW, warning that safety systems could not simply be abandoned.

Former energy minister Stuart Young questioned the removal of STOW requirements for state-owned energy companies, saying safety standards are critical, particularly for operations involving international partners.

“It does concern me because, of course, STOW certification is all about safety,” Young said.

He questioned whether STOW was a private or international requirement driven by multinational operators, noting that many energy assets had foreign shareholders who mandated safety certification.

What is STOW?

The STOW framework was designed as a pre-qualification system, requiring service providers to meet minimum health, safety and environmental standards before bidding for energy contracts. Certification was issued for one or two years, depending on assessment scores across several elements and a physical conditions tour of worksites.

On its website, the Energy Chamber explained that companies seeking certification were required to apply through the chamber and pay a series of fees. An application fee was payable to the Energy Chamber, with rates varying by membership status and risk category.