Alongside last week’s parliamentary election in Bangladesh, voters also cast their ballots in a national referendum on important constitutional reforms proposed for the country following the July 2024 uprising and ousting of former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina.

The July National Charter, which most political parties signed last year, was approved by 60.26 percent of voters.

But that vote has now exposed a schism between the victorious Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), led by Tarique Rahman, and the opposition, led by Jamaat-e-Islami.

On Tuesday, newly elected BNP members of parliament refused to take an oath as members of a new Constitution Reform Council, throwing the future of reforms into doubt.

We break down what the national referendum in Bangladesh was all about, why the country is divided on it and what happens next.

What is the context?

In July 2024, students in Bangladesh began protesting against a conventional job quota system, which reserved a significant share of prized government jobs for descendants of Bangladesh’s freedom fighters of 1971, now widely regarded as the political elite.

Hasina ordered a brutal crackdown as the protests escalated. Nearly 1,400 people were killed, and more than 20,000 were wounded, according to the country’s International Crimes Tribunal (ICT), which later found Hasina guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced her to death. She is currently in exile in India, where she fled after her ouster.

After Hasina went into exile, her Awami League party, which had been in power for 15 years under her leadership, was also banned from all political activities. The latest election was the first since the uprising.

Advertisement

What is the July Charter?

After Hasina was ousted, Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus took over as the country’s interim leader of a caretaker government in August 2024.

The July National Charter 2025 was drafted by the caretaker government, outlining a roadmap for constitutional amendments, legal changes and the enactment of new laws.

It contains more than 80 proposals to overhaul Bangladesh’s system of governance, with key reforms being “increasing women’s political representation, imposing prime ministerial term limits, enhancing presidential powers, expanding fundamental rights, and protecting judicial independence”, according to the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA).

The charter also recommends creating a 100-member upper chamber alongside Bangladesh’s current single parliamentary body, the 350-member Jatiya Sangsad.

The BNP was sceptical about the July National Charter referendum for months during the transitional government, at times signalling a “no”, until party leader Tarique Rahman publicly endorsed a “yes” vote on January 30 and the BNP said it would adopt the charter if approved in the referendum.

In particular, analysts say, the BNP appeared opposed to proposals to use proportional representation to fill the upper house, which, it has argued, could dilute large parliamentary majorities under the current electoral system.

Now that the charter has been approved, the new MPs must set up the Constitution Reform Council to enact the constitutional amendments in the charter. The implementation process is required to be completed within 180 days of forming the council.

Has the referendum caused division in Bangladesh?

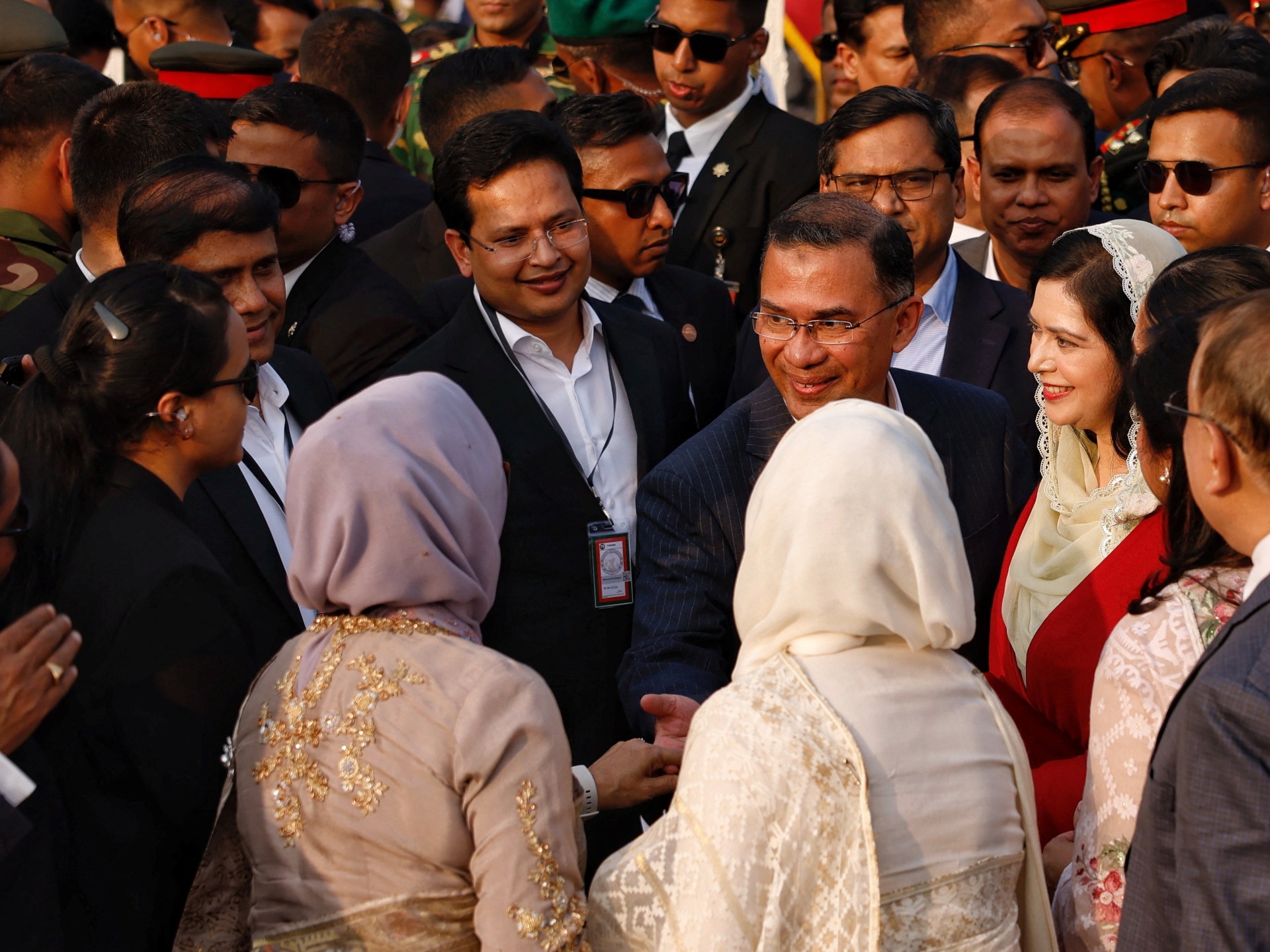

On Tuesday, newly elected members of parliament were sworn in.

They were asked to take two oaths. The first was the standard pledge to uphold the Constitution of Bangladesh. The second bound them to respect and implement the July National Charter 2025.

But the newly elected MPs from the BNP did not take the second oath, prompting criticism from members of Jamaat and its ally, the National Citizen Party (NCP), a party formed by students who led the protests against Hasina in 2024.

Under an implementation order that sets out how the July National Charter will be turned into law, the Constitutional Reform Council is to be composed of MPs who, at the same ceremony, also take an oath as council members. This technically means only the Jamaat, the NCP and a small number of others who took the second oath are currently eligible to sit on the Council.

Advertisement

Because more than two-thirds of the MPs did not take the second oath, the Council has not yet been constituted. It is unclear what will happen next regarding the formation of the council.

What is the main sticking point for the BNP?

Salahuddin Ahmed, a BNP standing committee member and MP, told local media after the ceremony that BNP lawmakers had refused to take the Charter oath because, in their view, the Constitution Reform Council, which will be charged with enacting the reforms, has not yet been approved by parliament.

“None of us have been elected as the members of this ‘Constitution Reform Council’. This council is not even a part of the constitution yet. It will be considered legitimate only when it is approved by the elected parliament,” Ahmed said, according to local media reports.

On Tuesday, however, he reaffirmed the BNP’s promise to enact the reforms: “We are committed and pledged to implement the July National Charter exactly as it was signed as a document of political consensus.”

The main concern the BNP is understood to have about the reforms relates to the formation of a second, 100-member upper chamber of parliament.

“Major parties appear to agree on almost all the core referendum issues. However, disagreements remain regarding specific details, particularly in regard to the formation of the proposed Upper House,” Asif Nazrul, a law professor at Dhaka University, told Al Jazeera earlier.

Bangladesh currently conducts all elections using the first-past-the-post (FPTP) electoral system. Each voter picks one candidate, and whoever gets the most votes in a seat wins it.

This can create a large gap between a party’s overall vote share and its actual share of seats. Theoretically, one party could win 51 percent of the vote in every seat, while another could win 49 percent in every seat. The first party would receive 100 percent of the seats, however.

Any party that wins at least 151 of the 300 seats can form a government alone, while the runner-up in seat count becomes the official opposition.

In last week’s election, the BNP-led alliance won 212 seats, followed by 77 for the Jamaat-led alliance, out of the 297 parliamentary seats for which results were announced.

The BNP wishes to retain the system of FPTP, but the July Charter recommends that the upper house be filled with representatives elected according to the proportional representation electoral system, which would give parties a share of seats more in line with their share of overall votes.

Forming the upper house in line with the FPTP system, by contrast, would put the BNP at an advantage due to the large proportion of seats it won in parliament.

“The BNP favours forming it [the upper house] in proportion to parliamentary seats, while Jamaat and the NCP prefer a system of proportional representation. Resolving this dispute remains a key challenge,” Nazrul said.

Related News

‘Torture, threats, rape’: Palestinian journalists detail Israeli jail abuse

Armed militia members are serving as Israeli agents in Gaza: Investigation

‘Nothing retaliatory’: US seeks deportation of 5-year-old Liam Conejo Ramos